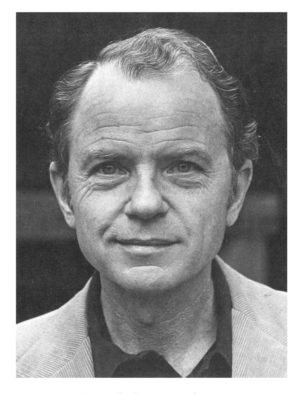

A century after a gaggle of French painters and poets launched a movement favoring dream logic and the most unexpected juxtapositions, Surrealism in poetry is still a thing. Much contemporary verse does or could fly that flag. But as tastes in poetry have veered toward the cautious and tendentious, it takes less and less—a few bold images, a couple of sideways moves—to stand out from the crowd. My thoughts go this season to the most thorough-going Surrealist I have known—one who never used the term—the fantastical Fred Ostrander (1926-2016).

Ostrander took an unusual path. A student of Lawrence Hart (and accordingly considered an “Activist” poet), he began with a long immersion in the discipline Hart made everyone start with, Direct Sensory Reporting. Hart regarded this stripped down yet highly detailed mode of descriptive writing as an essential prelude to more complicated work. Those who stayed the course agreed, yet mostly moved on as soon as they could to what seemed richer ground. Ostrander lingered, writing in this constrained manner for some five years, building up, I suppose, a kind of artesian pressure. Then the gusher came. “I went into a room,” he said later, “and went crazy.”

Access to dream landscapes? How about this:

Since you died I cannot bear my actions,

this eternal examination of the dark.

Your interminable walking far into my skull,

your heels growing small through the

dampness and the shining.

Or this:

But the memories. They are borne of the imagination,

angel and anti-angel, the flaring nostrils, dazzling eyes, dragon, skin of scabs

twisting like a dreadful tree-climbing vine, budless and without a song.

Or this about the crucified Jesus:

In the alcove he is hanging. Late he shines.

By moonlight like a waterbird he will stretch and rend himself

then climb with great stealth

back upon the nails.

It is clandestine.

He is lavender with shadow.

This begs to be compared with Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s celebrated, wisecracking “Christ Climbed Down,” written about the same time:

Christ climbed down

from His bare Tree

this year

and ran away to where

there were no gilded Christmas trees

and no tinsel Christmas trees

and no tinfoil Christmas trees . . .

After 50 years of strenuous Modernism, the times were apparently ready for something less demanding. Ferlinghetti became a power. Ostrander was denied the major recognition I think he deserved. He did have a lot of magazine credits and three books, one with a fine, small eastern house, one (an award-winner) with Blue Light Press, and a final New & Collected from Sugartown Publishing—but nothing that amounted to a breakthrough.

A wave falls, like the great initial verb, crushing upon the sand,

scattering like your countless pages the moments you were saving,

waves and the winds of the enormous, unpublished sea.

Not everyone would, should, or could write like an Ostrander. But whenever I find myself inclined to settle—to think: that line is maybe good enough, that image wild enough, that transition bold enough—his best poems are touchstones. I read them, and I am ashamed.

Some copies of Ostrander’s books are available. Contact staff@lawrencehart.org.

so wonderful to be reminded of Fred’s genius & a pleasure to read the lines you included! I will read him again after a long hiatus to help me on my way!

Thanks John – well done 👍