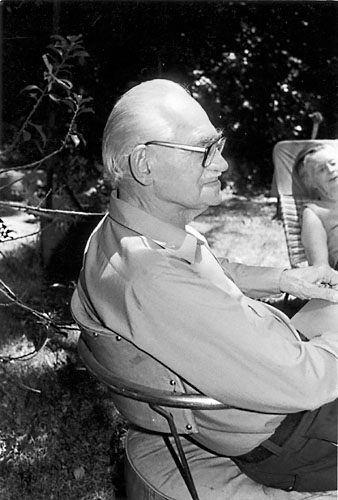

I write here as someone with two special angles of vision on the poetry world. One comes from twenty-odd years as an editor—and three as sole editor—of the durable West Coast all-poetry magazine Blue Unicorn. This job entails constantly sampling, and choosing from, a hefty stream of submitted verse. The second is a lifetime of immersion in the critical ideas and teaching methods of Lawrence Hart, mentor of the so-called Activist Group of poets, and my father, who died in 1996. For a quarter century now I have been documenting, applying, and I hope extending these methods.

The elder Hart believed that there is, within the great mass of writings called poetry, a small subset that shows the powers of language being used to their fullest—and that, in the long run, this is the only kind of poetry worth trying to write: the poetry that matters.

I believe this, too. As a poet myself, I know how far and how routinely I fall short; but I also insist on measuring my efforts against this ambition, hoping, at least, for some interesting failures.

In another part of my life I have been a mountaineer and rock climber, so I’m drawn to landscape analogies. The strongest poetry rises above the plains of language like a mountain range; it stands apart from the settled landscape of prose like a wilderness area. It is not always easy of access, either to the writer or the reader. Yet there are trails, routes upward and inward, for both, and the views, to push the analogy, are grand. Poets of every era have made paths. I believe that my father, as he helped a number of noted poets to strong individual styles, found one particularly promising trail.

But to make one’s way toward the core regions of poetry requires one thing first: a recognition that there are core regions; that not every poem, just because it is called a poem, is interesting or rewarding; and that there is, damn it all, a real distinction still to be made between poetry and prose. This itself is a not uncontroversial idea these days.

“Poetry” is a funny word. It doubles as the descriptive name of a type of writing (just what is it? Much to talk about) and as a term of praise. Nobody hesitates to say that there are good and bad novels, good and bad plays. Invoke the magic word “poetry,” however, and critical tongues get strangely tied. Just a few strong voices—John Logan and Clive James come to mind—are sometimes heard above a soothing murmur of mutual approval.

So one purpose of this blog is to highlight critical insights I encounter, and to add some of my own. As far as any one person can, I watch the unfolding poetry scene in English, French, and German—and a bit of what filters in from other languages via translations—with keen attention and, too often, equally sharp disappointment. I have formed and tested some strong opinions. I plan to share them here. These ideas will be debatable. I hope to excite some debate.

I’m so pleased to see you talk about the Activist legacy–it is a missing chapter of California literary history.

As an ‘activist ‘ poet, you’ve already got me interested in this debate. I’d love to hear the next installment .. totally agree so far. In my two (modest) collections my forward puts out my ethos. One thing I say is its fine by me if you like this one and not that one. And I agree, protocol dictates that you don’t critique another poet’s work.

Anna Meryt

Anna Meryt

I agree. Lawrence Hart did important work that too few know. It deserves wider celebration