Somebody dropped the E-bomb. A submitter to Blue Unicorn—advised he would do better to try his luck elsewhere—accuses the magazine of being “elitist.” The jibe started me thinking about this whole question of elitism—and the quite different fact that there are elites.

Quality, after all, does count. We salute the pitcher with the most wins, the surgeon with the best outcomes, the lawyer whose arguments persuade, the climber who can actually make it up the route. In the arts, granted, it gets murkier, because the standards of judgment are constantly under debate. I may think recognition goes to the wrong people. But that doesn’t mean I’m against the recognition. Like the Biblical poor, the elites ye will have with ye always.

Elitism is something different. It’s the feeling, among those who have somehow made it, that very few people can, or even should, follow them into that state of grace. Some earlier writers I admire were outspoken in this view. “I’m asked if I think the universities stifle writers,” said Flannery O’Connor. “My opinion is that they don’t stifle enough of them.” “Art is rare and sacred and hard work, and there ought to be a wall of fire around it,” wrote Anthony Burgess. More recently, Kay Ryan has struck a similar note.

The contrarian tartness of these statements makes me smile, but I don’t agree with them. It’s not that there should be a wall of fire to overcome in attaining the highest level of any skill; it is just that there is such a wall. Some few may find their own way through it; why not give an assist to many more? Universities may or may not be doing a good job of helping people penetrate the wall, but it is all to the good that they try. If they try. My own experience, of the creative writing program at Princeton, gave me an early shot of skepticism about that.

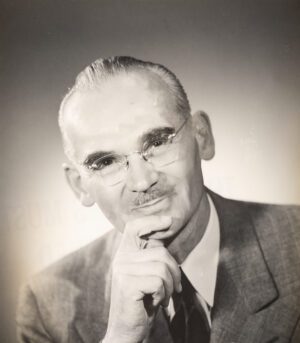

Lawrence Hart, a poetry teacher unblessed by the academy, embodied a third way: not permissiveness, not exclusivity, but what you might call open door elitism. He demanded a great deal of his students, and criticized their work severely at times. But he adopted the principle that anyone who came to him had the potential to achieve mastery, and he threw himself into the effort to help them achieve it.

He once asked a student if she would be jealous if too many people joined the “elite” of really fine writers. The risk of this happening seems not very high, but such was truly this great teacher’s goal. The nonprofit organization named for Hart is dedicated to opening doors like the ones he found—to people selected only by their willingness to enter.