It’s a little late to be noting the centenary of T. S. Eliot’s still fascinating poem The Waste Land—published in book form in December 1922—but two of the many reactions called forth by that anniversary are on my mind.

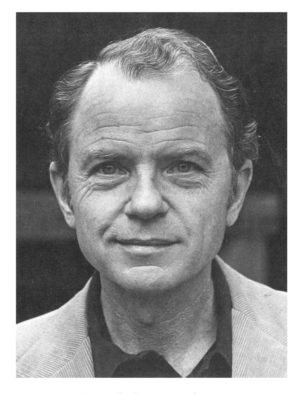

One is Jed Rasula’s book What the Thunder Said, issued by Princeton at the end of the year. Despite the Eliotesque title, it’s really about the whole sweep of literary Modernism, a story that Rasula starts, convincingly, with the music of Richard Wagner and its novel way of handling and interweaving themes. The second is Matthew Walter’s article “Poetry Died 100 Years Ago This Month,” which appeared in the New York Times on December 29.

Both critics have intriguing things to say. But I was most struck by their takes on the influence of the Eliot poem: ideas that are just about opposite to one another and, I think, just about equally wrong.

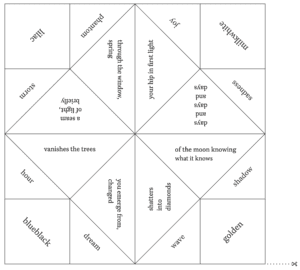

In The Waste Land, a depiction of lives and civilizations gone bad, Eliot cuts rapidly from scene to scene. He zestfully mingles the classical and the plebeian. He brings in things he has read, heard, and seen, from various traditions and in multiple languages. It’s a kind of collage, Rasula observes, and he reminds us that other writers of the era were also experimenting in this fashion. (Not so unique, after all? But why is this particular word collage the one we still talk about?)

When it comes to influence, Rasula traces the Eliot effect through midcentury and beyond, finding no sharp break between the Modern and Post-Modern. In a linkage that would have startled both men, he sees a straight line between The Waste Land and Allen Ginsberg’s no less gloomy Howl. “Taken by some at the time as a rebuke to The Waste Land, with hindsight [Howl] was clearly an idiomatic update of Eliot’s vision.”

Really?

Matthew Walter sees potent influence, too, but regards it as entirely harmful. “The clipped syntax, jagged lines, the fixation on ordinary, even banal objects and actions, the wry, world-weary narratorial voice: This is the default register of most poetry written in the past half century, including that written by poets who may not have read a single line of Eliot . . . . The problem is not that Eliot put poetry on the wrong track. It’s that he went as far down that track as anyone could, exhausting its possibilities and leaving little or no work for those who came after him.”

Again: really?

I love The Waste Land. Who could or would do just that thing again? But that’s not to say that the poem contained or foreclosed all ways of doing poetry. W. H. Auden, for instance, benefitted from Eliot’s support but wrote not a bit like him. As for Ginsberg, Kenneth Koch, and the other anti-Modernist torchbearers of the 1950s, they were not imitating Eliot in any meaningful way. They were angrily turning their backs on the skills and demands he represented. They thought they were repudiating him. They were.

The Waste Land is indeed a classic. In these critiques we see two, well, classic reactions to such an overwhelming model. One is to claim its sanction (“We’re all doing the same thing, after all”). The other is to use it as an excuse (“Who could possibly rise to that level now?”)

Slipping back an additional century, I’m reminded of John Keats’s complaint in “Sleep and Poetry” (1817): “Is there so small a range/In the present strength of mankind, that the high/Imagination cannot freely fly/As she was wont of old?”

Well, of course she can.